Intro

Producing an audiobook to be at a professional level is a big undertaking. It involves hours of recording, gigabytes of data, and exacting specifications. I’ve spent a lot of time understanding these and iterating on my process as I went through the full pipeline as narrator, sound engineer, producer, and publisher for my wife, Jern Tonkoi’s bittersweet romance novel, Lanta. I’m now revisiting it all as I embark on Jern’s other novels.

In this article, I’ll lay this out in a structured manner, giving my choices and the reasons for those choices. I will go through in chronological order, apart from starting with the very most important element, the end goal.

Product specifications

I’m aiming for a professional audiobook and, whilst many standards exist, Amazon’s ACX requirements appear to be the de facto standard, with all others I’ve come across such as Spotify and Apple falling within those. ACX requires the following:

- Peak levels are less than -3 dB

- Noise floor is less than -60 dB

- Volume is between -23 dB and -18 dB RMS

- 192 kbps or higher CBR

- Mono or stereo

- …and some others related to perceived quality, such as consistency and no mouse clicks, etc.

Decibels

Now, I’m a physicist, and even I don’t like decibels, or dB, but let me walk you through it to the extent it is useful for someone about to record a professional-quality audiobook.

A decibel is a way to measure sound that is actually just a comparison. It’s not like kilograms or metres, it just compares.

So, how is this useful?

Well, we start by saying that the maximum possible amplitude in an audio track is 0 dB.

This means all the audio that is not at maximum amplitude must be less than 0 dB, which means it is always negative.

Point 1

So, by Point 1, enforcing that the peak levels are less than -3 dB, ACX is saying that the loudest thing in your file cannot be more than -3 dB. So, it will reject you if you have a peak that is -2 db, -1 dB, or 0 dB.

What happens if you go above 0 dB? Well, since 0 dB is the maximum possible amplitude in the audiotrack, going above that will be recorded as 0 dB still (which is very loud, remember), and this is what we call clipping. You tried to go to +1 dB, but it was clipped and saved as only 0 dB, the maximum possible amplitude in an audio track.

What is -3 dB in real terms? Hmm, define ‘real terms’. Mathematically, dropping to -3 dB reduces the amplitude by about 30%, which seems huge. But, our ears also work oddly, or logarithmically if you prefer, and the change is barely perceptible.

In other words, limiting the peak level to -3 dB means we are not clipping at all, but we are still near the maximum possible amplitude.

Point 2

Point 2 says we get the noise floor less than -60 dB. This means the amplitude of the background noise is 99.9% lower than your voice. That’s pretty darn quiet. It means you cannot have a fan whirring in the background, or if you do, you’d better use software to remove it.

Pro tip: try not to rely on software to remove anything.

This is why it is useful to understand the goal before starting. Skipping the step to remove noise from your recording setup will really come back to bite you.

Point 3

Point 3 is more challenging to fully understand, but luckily we don’t need to. Volume must be between -23 dB and -18 dB. That’s a nice, wide range and by now we know that -23 dB is the quietest volume and -18 dB is the loudest volume allowed. But, what is volume, when we already had peak level? It’s essentially a measure of how loud the audiobook feels. If you listened to two audiobooks, one after the other, you wouldn’t want to be adjusting the volume of your iPhone. You’d want them both to be playing at the same volume, more or less. So volume here is a measure of how loud your entire audiobook is, and has a lot of maths behind it (RMS or root-mean-square maths to be precise). Best to just leave this till later really, and this time use software to master your final output to meet this standard.

I think of it as getting the peak levels up to near -3 dB, then squishing or spreading out everything else (compression) until the calculated volume is in the range.

Points 4, 5, …

Then we have Points 4 and 5, which tell you to have at least 192 kbps constant bit rate, CBR, and to make it mono or stereo. Since some places want mono, I stick to that. And I output at the max 320 kbps since storage is cheap.

The other Points are all related to technique really, which I covered to some extent elsewhere.

So, now we know the goal, let’s get into my process.

Software stack

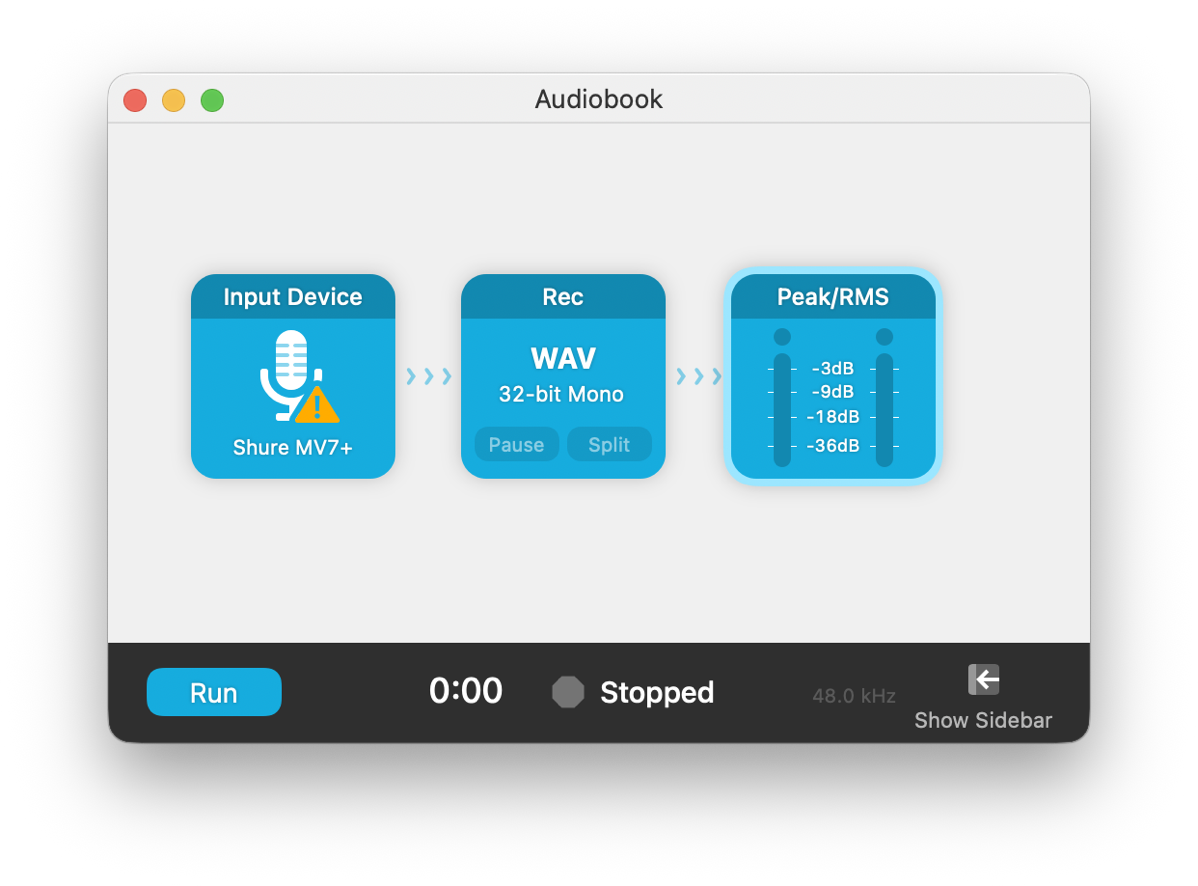

My main advice is to use what you are comfortable with, or spend time to get comfortable with something. Personally, I use Audio Hijack for recording, iZotope RX11 for processing, Logic Pro for production, and I’m still wavering between various options for mastering.

For my software and my workflow, I try to keep a focussed directory structure. I have a directory for each audiobook, and within those I have directories for:

File/Dir structure

- Original WAV files

- Cleaned RX files

- Enhanced RX files

- Logic Import files, which are the WAV exports from RX

- Logic Bounce output files

- And alongside these, there is my Logic Pro file

Starting point: The Original WAV file

As mentioned, this is not as critical as you might think. You should try to get the highest quality, refer to my previous article for much more on this. But beyond that, just record at 44.1 kHz, 32-bit float, and save as WAV. With that, you have more than enough headroom to do some editing and not lose too much quality.

The key thing, though, is to store this away somewhere. Don’t edit it. Keep it somewhere, back it up, and make a copy to work on. Doing this means that if something goes wrong, you can recover. If four months down the line, a new bit of software makes your edits sound amateur, you can start again.

Personally, I put the original in the Original directory, then work on a copy in the next step.

Processing Pass 1: Cleaning

The goal of the step is to get the audio in to a position that will allow the production step to be done effectively.

At this stage, we want to do as little as possible so that we never need to go back to it, but I’ve found that a little tidying up can make later tasks much more manageable. So, what do I do?

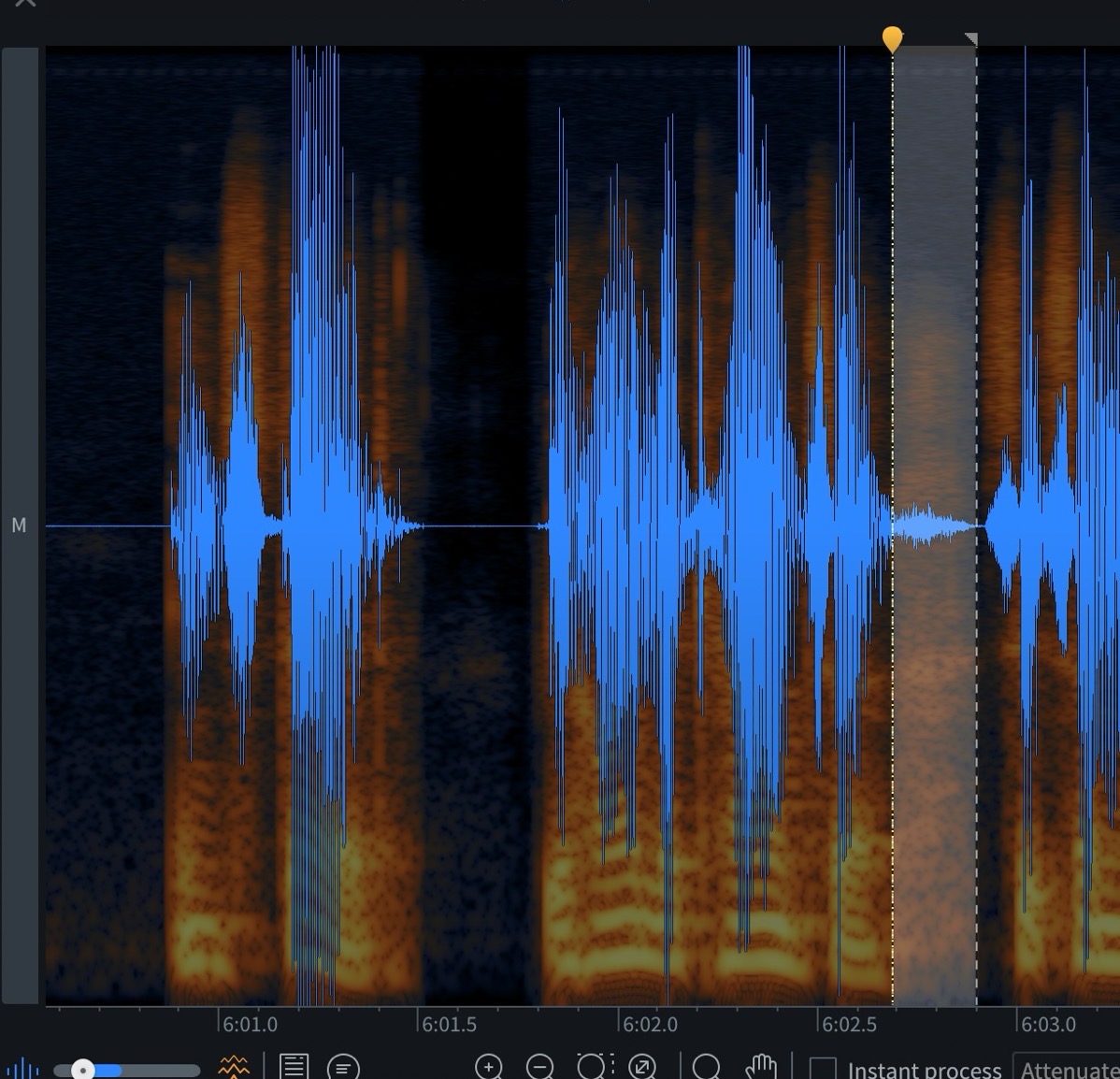

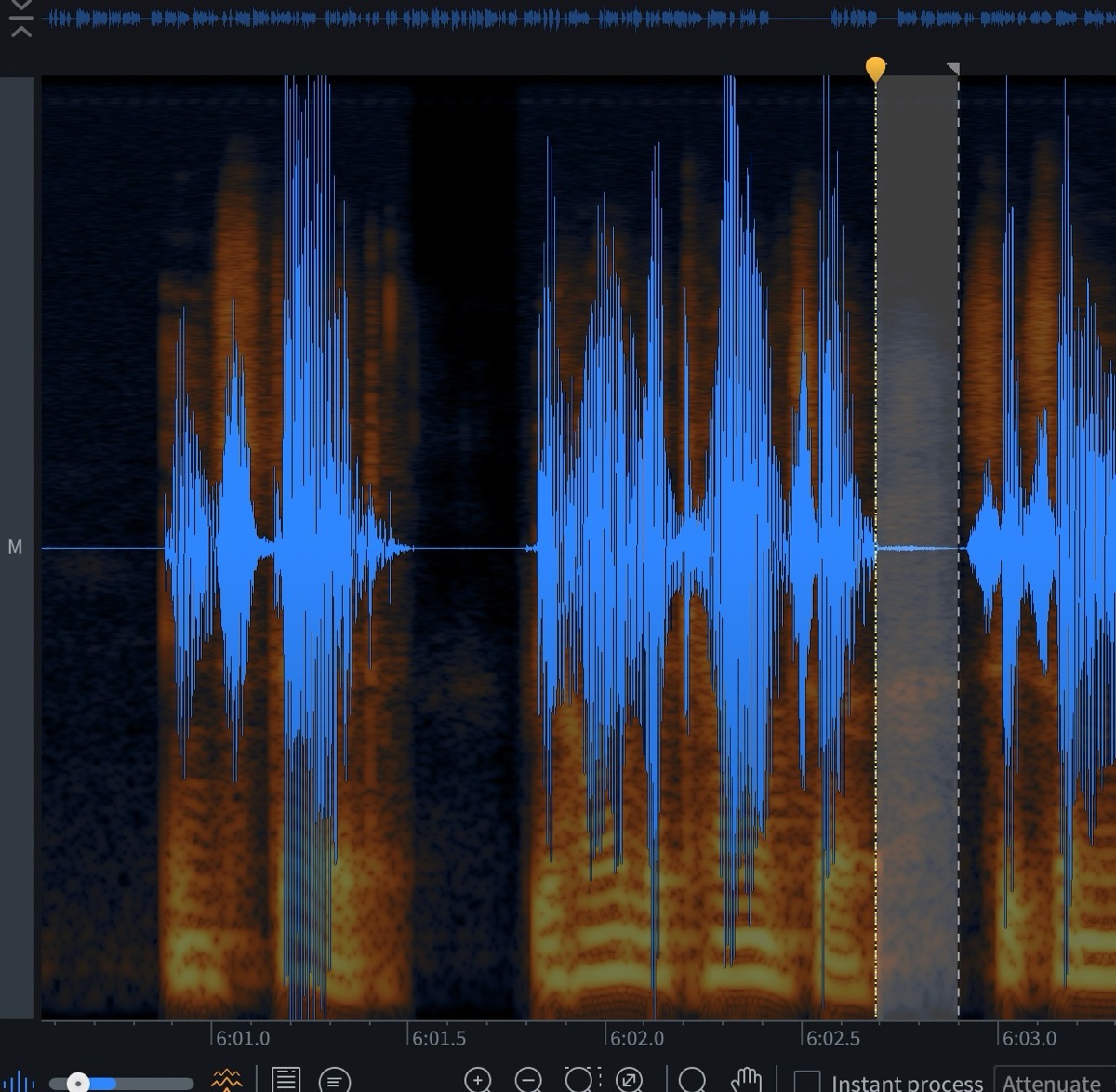

Currently, all I do is bring the audio file into iZotope RX11 and zoom right in to the waveform shown on the screen. You can use other tools, but RX11 has a really good display of the waveform that lets me see what is going on. It gives me a great zoomed-in look.

I then listen through, and use the Gain tool and do the following:

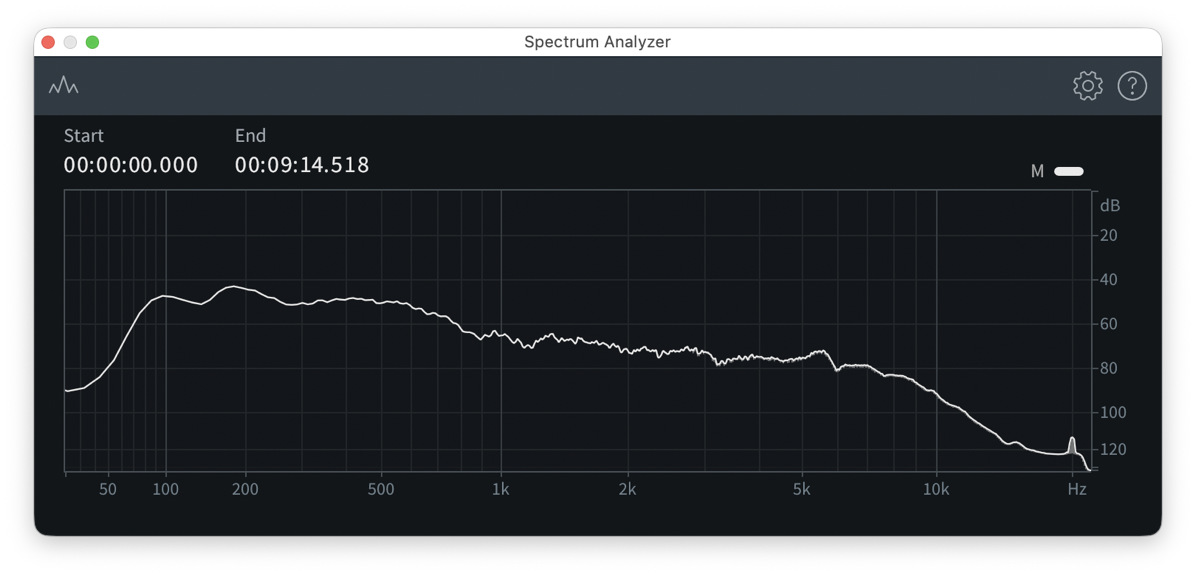

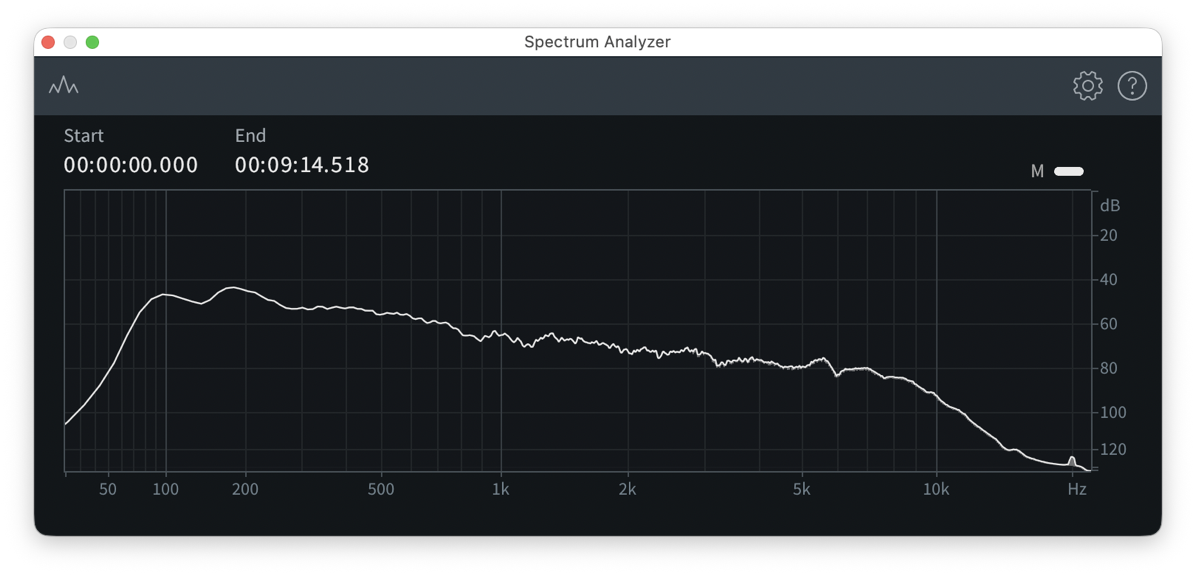

- Reduce the loudness of any strong breath-intakes that got into the recording. In the image, the waveform shows me saying, “Instead (pause) behind the counter (breath) sits…“. The first image shows the waveform with the breath, the second shows it after reducing the gain. The result is fewer annoying breath noises. Notice how I didn’t strip it out completely, just reduced it massively so that the listener will never notice anything odd.

- Reduce the loudness of any fluffs or external noise. Sometimes, when reading I make a mistake, pause, and re-record a line. I want to remove these and so when I hear one I go in, select the fluff, and reduce the gain. Here I reduce it three times to really get the loudness down.

Doesn’t this leave long gaps in the audio? Why not delete it?

My method keeps the file length unchanged, meaning that if the original WAV file for Murder in Treggan Bay chapter one is 10 minutes 14 seconds long, the edited file is still 10 minutes 14 seconds long. This will make it easy to make adjustments in future. It provides a path for me to come back and improve my initial edit (maybe I accidentally removed the wrong bit) and not necessarily have to start all over again. This will become a bit clearer as I talk about the later stage using Logic Pro.

And that’s all I do right now. I don’t use any of RX11’s other lovely tools yet, I just make myself a cleaner version of my original file with fewer distractions and save the RX file in the Cleaned directory.

Processing Pass 1: Enhancement

I get a little bit weird now, because my next stage is to make a copy of that RX11, and put this in the Enhanced directory.

My reasoning has some sense to it. I see the last stage, the gain adjustments, as providing a clean version of the file without any processing done. In future, I might use a different tool to do it, so I want to keep it separate. I had my original audio file, I created a clean version of it, and now I’m going to process it.

This processing is much more subjective and tool-dependent, so I have isolated it.

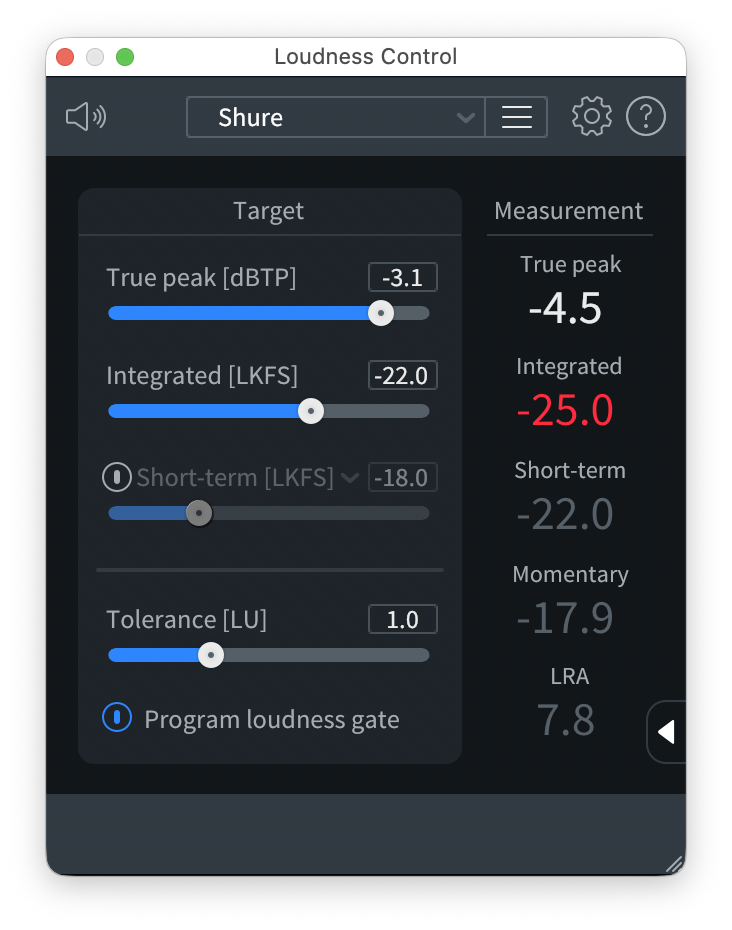

Again, there will be no cutting or anything that will change the file length. What I will do is use the tools available to process the audio more strongly. In RX11, this means using tools such as De-click, Mouth De-click, Voice De-noise, and De-ess. I don’t use the EQ at the moment, but I do use Loudness Control to bring the loudness up to -25 dB. At the end it will go up some more, but this gets it fairly standard and leaves some headroom.

I export this clean and clear audio file into a directory called Logic Import, the labelling clearly telling me that this is the file to use building my audiobook.

All this time, I stick to my 44.1 kHz, 32-bit float WAV file so I don’t worry about losing quality. Modern computers can handle this quite easily.

Production in Logic Pro

Logic Pro by Apple is not really designed for audiobooks, but it works well for me.

Here’s where my insistence on never changing the file length and leaving long silences can start to make sense.

Logic, and many other similar pieces of software, is designed to work with external files. I have a folder of audio files in my Logic Import directory, and I am going to import them into Logic now. However, I have it set so that Logic does not move these, it leaves them in place. This can work magically. Let’s say I imported 40 audio files for 40 chapters. I then did a whole bunch of work in Logic. I then realise I can do a better job cleaning or processing the audio file… what to do? Well, I can close Logic, go back, redo the processing in RX11, put the new file into the Logic Import directory with the same filename, and when I open Logic it will see the new version and apply all my Logic edits to it. I don’t have to redo a thing in Logic. That’s magic.

Now you know why I never trimmed or cut my audio files, because if the length of the original and the new processed files changed, Logic would be terribly confused. Like this, it never even notices.

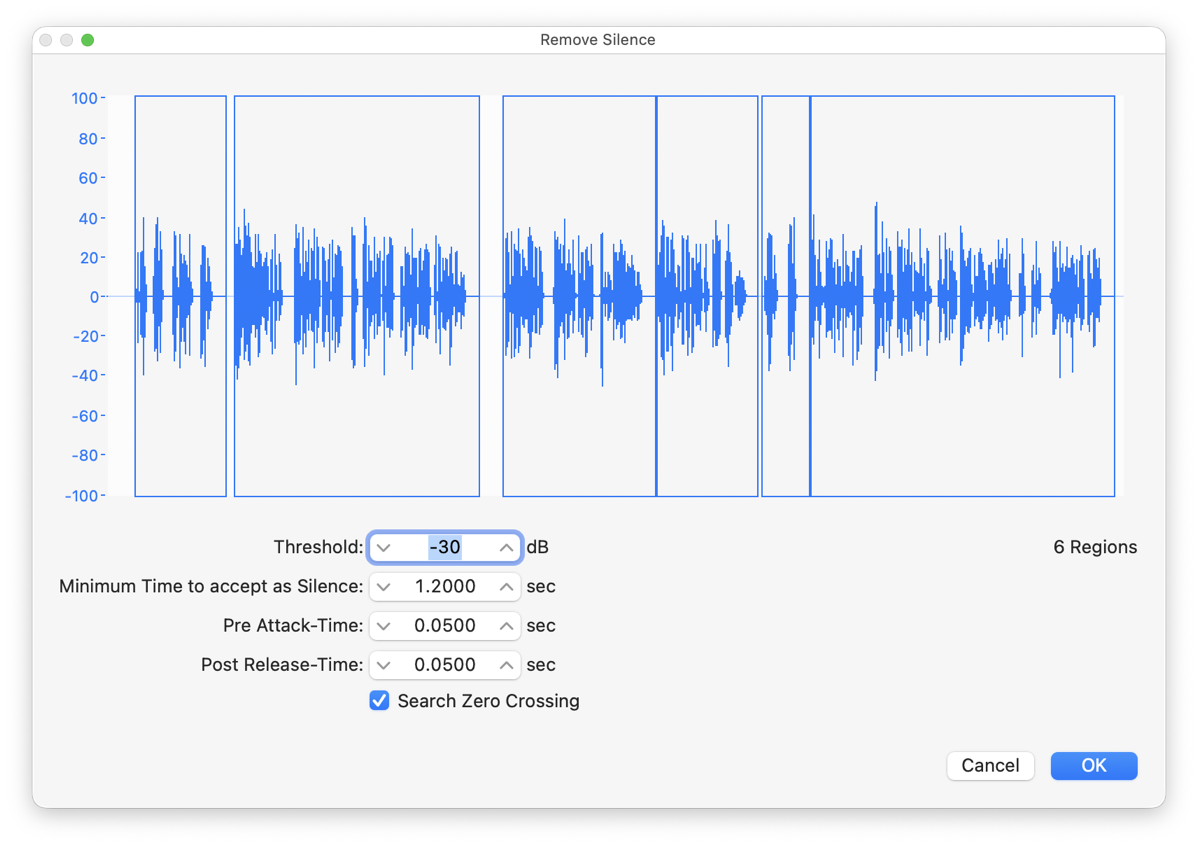

What about the long gaps? Logic has a great tool to trim silences.

When I import a new audio file, I select it and hit control-X to bring up the trim silences dialogue. In there I can set the level to consider as silent; I use -30 dB, so anything lower than -30 dB is considered silent. You can also set the minimum length of silence, which I put at 1.2 seconds.

- This means that if the audio’s volume drops below -30 dB for 0.8 seconds, nothing is done.

- But if the audio’s volume drops below -30 dB for 1.4 seconds, then it will be trimmed to just 1.2 seconds.

- And if one of my fluffs now means there is a gap where the volume drops below -30 dB for 47 seconds, that too will be trimmed to just 1.2 seconds.

And this is all done automatically.

There are also settings that affect how abruptly the corrections are made, which I set to 0.05 seconds.

After accepting these settings, I have not one section in my timeline, but many with gaps in between that used to be long silences in the audio. Now they are gaps, so I can use the command to shuffle these to the left so that they touch, removing the gaps. I then scan through to see if there are any silent sections I should delete, and I’m done.

I might now choose to Join these again to keep it all tidy.

Handling Chapters

Logic Pro is great, but it is not designed for audiobooks and so doesn’t handle book chapters gracefully. I don’t want to spend money on more software though, and I have found a workflow that does the job nicely.

Firstly, each chapter is its own separate track. I can then choose which track is playing and have all the others muted. This is a bit manual, but you get used to switching easily enough.

Audiobook specifications tend to like some room noise at the start and end of each chapter, half a second to a second or two. Essentially, even quiet recordings are not 0% noise, and to jump to and from that can be noticeable by some. Instead, it is better to have a little, teeny bit of room noise fade in at the start, and a little, teeny bit of room noise fade out at the end.

So, from one of my recordings, I create a short region of room noise and place it at the beginning of the track. I then have the narration. And then I have another region of room noise.

In addition, I might find I have gaps in my track. For example, my previous trim silence might have been too much when I wanted a longer pause for effect, so in Logic I would have shifted all the regions around, leaving pure silence. To remedy this, I make another track that is filled from start to end with room noise. If I just enable it, I could be doubling up the noise, so I don’t want that. Instead, Logic has a function so that this room noise track only plays when the main track is silent.

Technically, we are applying a noise gate as a ducker. The settings make the room noise channel mute itself by going to -100 dB when the chapter’s channel is above -50 dB. We set the chapters channel by selecting the Side Chain to be Bus 1 at the top-right of the dialogue, and by sending the audio from the chapter to Bus 1.

It’s hard to explain, partly because I’m not certain I understand it myself, but it does mean that my audio never goes to true silence, it only goes to very, very quiet.

Final Polish

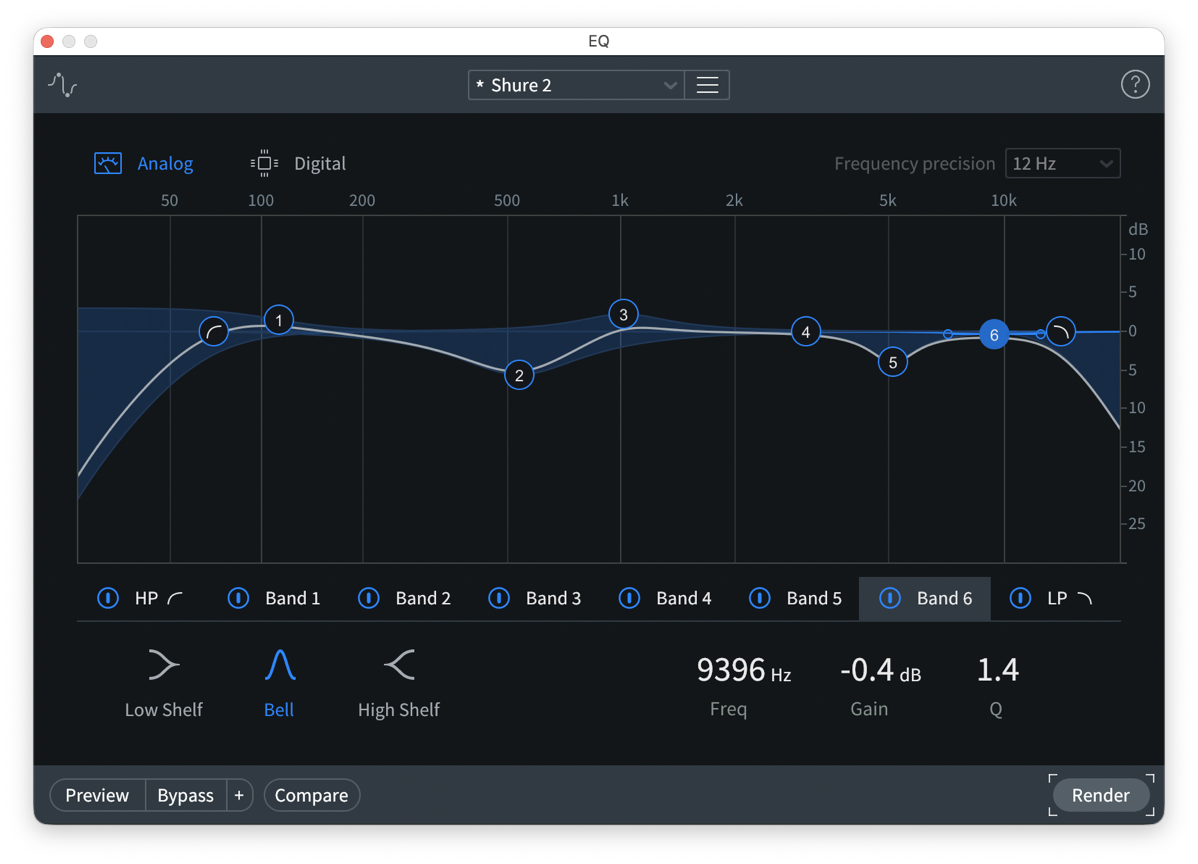

Now it is all lovely, you may want to make final adjustments to the sound quality, so starting with the EQ and maybe compression and limiters and other things a fully trained sound engineer knows what to do with.

I don’t.

It’s all a bit of a black box to me, meaning I tend to over-produce and make things worse. Happily, this is another area that ChatGPT can help with. Firstly, it gave me the stupendously wonderful suggestion of taking audio samples of some professional audiobooks that I admire and analysing them. Find out what their overall frequency patterns look like. It turns out, the ones I liked tended to have a gentle slope downwards from low frequencies to high frequencies. My recording, on the other hand, had plateaus and sharper drips.

To fix it, I put an image of my recording into ChatGPT, and an image of a reference recording, and asked ChatGPT how to get from mine to the reference. After a few attempts, I got there and it actually worked to make my audiobook sound better.

To get the EQ settings I want, applied some classic trial and error. In the original audio, I noticed that around 500 Hz (the bottom axis), the audio seems to have a little bump up. So, in my EQ, I applied negative gain at that point. Similarly, around 5000 Hz was a bit high, so I dropped that too. The results seemed good and only a slight shift, so I think I did it right!

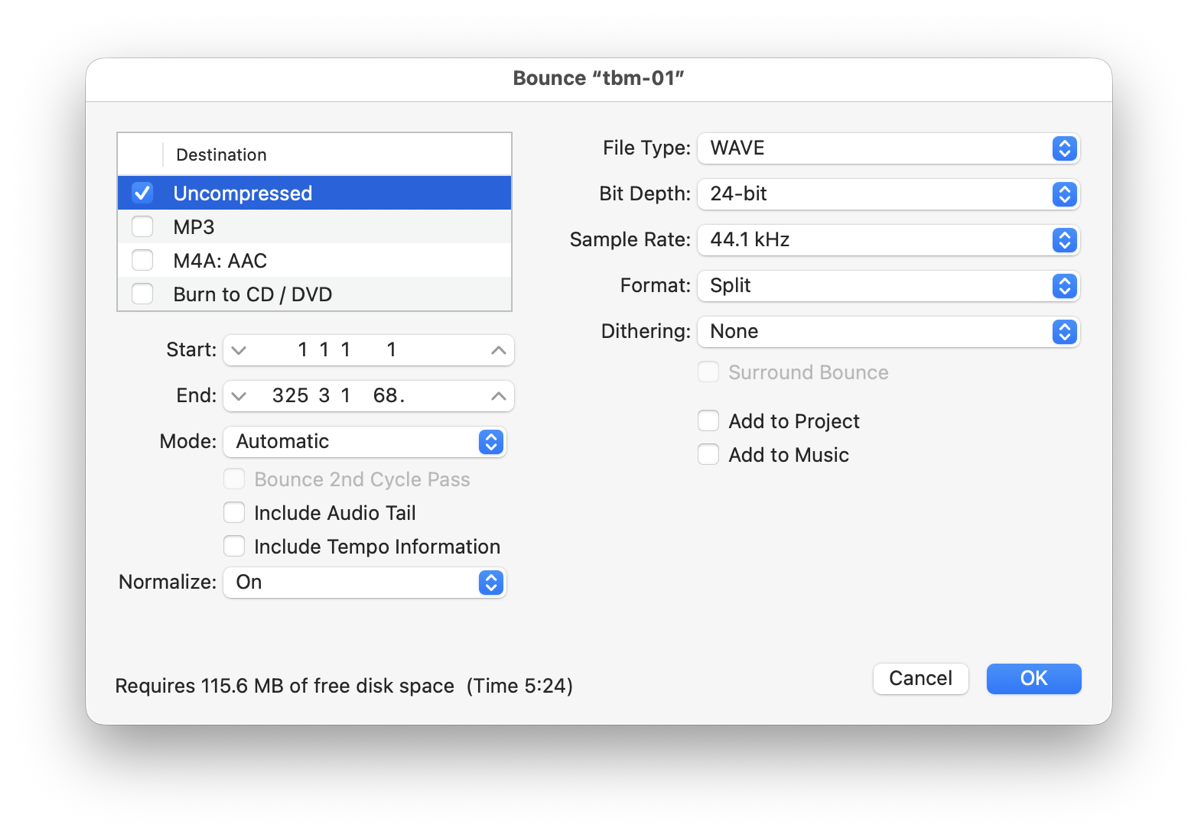

Exporting/Bouncing

Exporting the audiobook is annoying, but I decided that given the hours and hours of narration and production that have gone into this, I won’t begrudge it. Too much.

To export, I select a chapter and the room noise channels to play, set the length of the selection, and choose Bounce > Project or Section… in the menubar. This gives me my options for output, and I can save the file to disk. Since this is the end point, I can choose settings based on audiobook standards. I go for an uncompressed mono WAV still at 44.1 kHz, but 24-bit Bit Depth. To get mono, I have to choose Format: Split, which gives me Left and Right output files. I delete one of them.

I then deselect the chapter, select the next, and bounce that. It takes time, but it’s worth it.

Final specification pass

To be honest, I’m still playing with this to find my long-term solution.

First off, though, Audacity is able to help analyse a file and check if it is ACX ready. However, I did find that fiddly for some reason. Maybe it’ll click next time.

RX11 can be used to analyse and adjust loudness, because that’s basically all that is left.

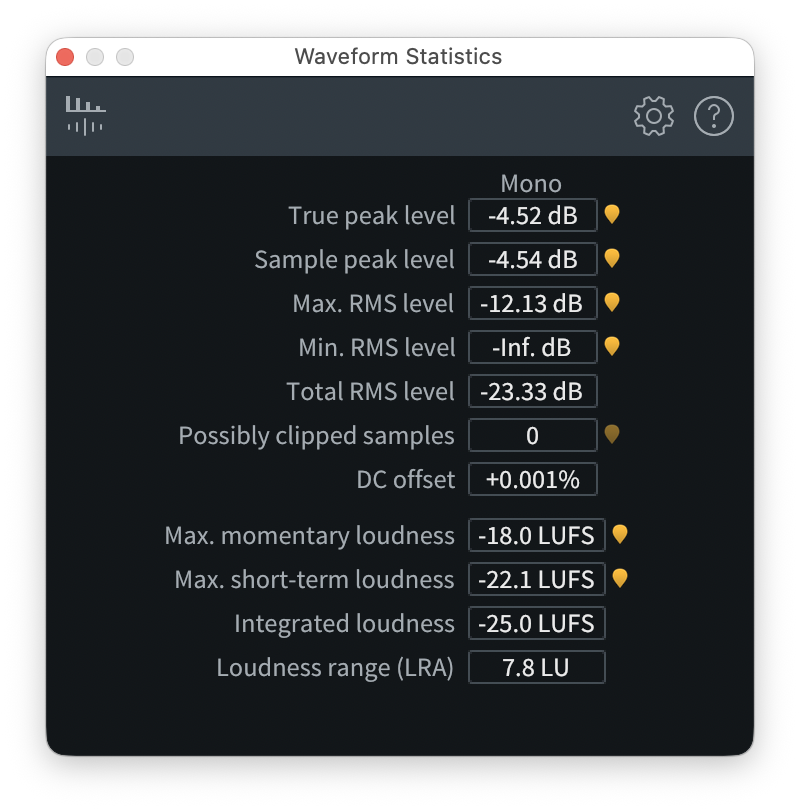

There is a screen to show values for all sorts of things, and with the help of ChatGPT it all makes some kind of sense. The key value is probably the Total RMS level, which for me normally needs a bump up since I was always staying safely below 0 dB earlier. In this screenshot I am at -23.33 dB, so below the minimum of -23 dB. I will use the Loudness Control tool to bring that up, and then check if everything else is still within range.

Again, this is a bit of a black box to me, but ChatGPT and some trial and error can sort things out. Remember that AI can understand screenshots, so take one, put it in the chat and ask, “Does this file pass ACX?”

In the end, if your file sounds great to you then you can upload it. If the service complains about LUFS or Levels, come back to your final exports and tweak them. Once you know what works for your software and the service you are using, then record it somewhere for future use. There’s nothing to lose here.

Listening

Now that the audiobook is finally finished, it would be tempting just to ship. But, anything could have happened, including accidentally skipping a whole scene. So, please, please, please listen to the whole thing again. You’ll enjoy, honestly. Just be patient.

Recap

To bring it all back around, let’s remember that the goal is to produce an audiobook that meets the specifications required.

So, start by being clear what all the specifications are, including the need for low background noise, and think about whether you can meet them.

Then, decide on your complete workflow for production. Make sure you know what software you will use and what it will do at each step, to get you from a voice recording to a fully-produced audiobook. By mapping it out, you can make sure you have all the pieces, and you can also make sure you have all the connections. And, you can try to optimise the flow so that you if something changes, you can recover without having to go back and rerecord.

I outlined my flow to help you.

- I record in Audio Hijack to get a high quality wave file.

- I never trim or delete bits of this, but I then use iZotope RX11 to clean the file, making my breath-noise and my fluffs silent.

- I then use RX11 again to process the audio with tools such as De-click and De-noise.

- I then put all the chapters into Logic Pro and trim silences, or extend silences, and get the chapter sounding just right. I’ll apply gain to individual regions as needed to get the feel just right.

- I’ll then run an EQ on it to get the tone how I want, and do a final Loudness run to get the audiobook matching the specifications.

Your flow might use different software, or have a different structure, but what I’d like you to take away is this:

- Design your workflow from start to end before you begin, and test it.

- Make sure your workflow does what you expect, and that it is scalable. It must work not just for a five-minute test, but also for a ten-hour audiobook.

- Be prepared to spend 40 hours or more working on a 10-hour book, not including the learning process.

If you want to know how I get along, come and ask me over in the Slack community at podfeet.com/slack, where I and all the other lovely NosillaCastaways enjoy friendly, positive online conversations, if you can imagine that. Feel free to message me, Eddie Tonkoi if you have any thoughts or questions or examples of doing it better than me.

You can also find our work at jerntonkoi.com, where you can find Jern’s books, audiobooks, and bonus material for our subscribers.

I’ll be back soon to talk through some of my editing workflow, but for now,

happy listening, and happy reading.